By Ludovica Cipolla

Legacy is an act of hope, and of love. At its heart lies the urge to make sense of one’s life by passing on what ultimately remains beyond our control and interpretation.

We’ve explored what it means in the cradle of Swahili culture, through the lens of three Lamunians, by birth or adoption. We asked ourselves: what must we pass on, and what is worth leaving behind?

Legacy to Soudy

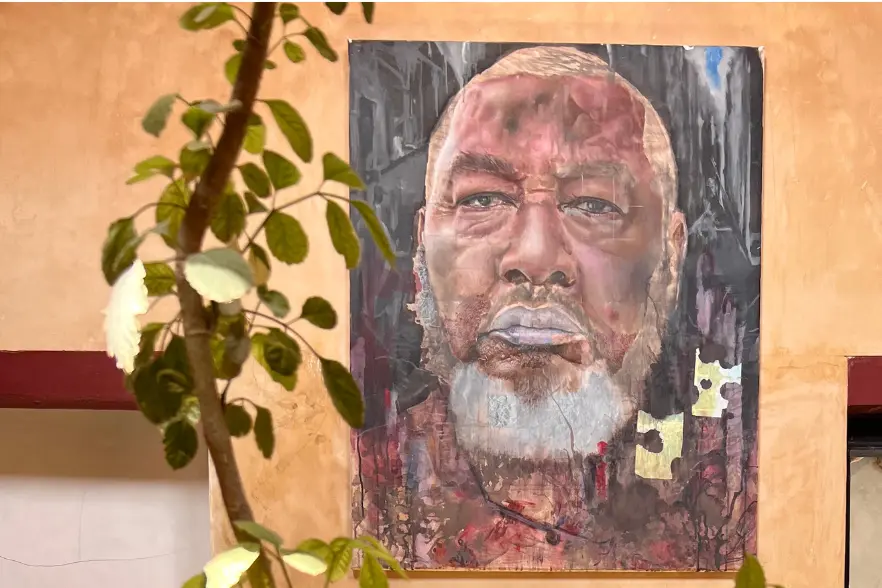

Soudy, a young architect and mixed-media artist, recently renovated a four-room apartment in the Old Town, a reflection on legacy itself. The Swahili sequential room plan remains intact, but new light filters through the ceiling and upper walls. The space also serves as a small gallery, where his and others’ works hang sparsely among simple chairs and cushions. A close-up portrait of his father stands out amid abstract art and street scenes. “Legacy to me is combining uniqueness and revolution. I painted my father during a time when I valued family deeply. Before I knew the greats who shaped my art and architecture, he was the first to validate my work… always there at my drawing table, silently following my brushstrokes.”

Legacy to Christina

Christina first arrived in Lamu in 1974 as a young Swedish woman and quickly developed a lifelong fascination with Swahili culture and poetry. In 1990, she and her husband Paul returned and, on a whim, bought a historic Omani house behind Lamu Fort, once the governor’s residence under the Sultan of Zanzibar. They named it Subira House, which means patience in Swahili. Known as Mama Subira, Christina turned it into a beloved eco-rated guesthouse. “Legacy is about joining tradition and innovation. We’ve honoured it through restoring traditional buildings, first in Sweden, then here. We never compromised: caring for the environment, healthy living, and beauty guided us. Everything should please the eye. And we’ve learned from local values; let things come together in their own time, never push, let them unfold naturally.”

Legacy to Hassan

The Flipflopi Project, founded in Lamu in 2018, shows legacy as reinvention. It built a dhow, a Swahili sailing boat, entirely from recycled plastic, turning waste into a symbol of environmental responsibility. Building on this, engineer Hassan Shariff now helps design recycled plastic furniture inspired by Lamu’s iconic forms. “The Flipflopi legacy extends far beyond the world’s first recycled dhow. It lives through the recycling centre in Lamu, linking plastic collection, boat building, furniture making, and community education. I support this legacy by creating new innovations to tackle plastic pollution through research on recyclability.”

If legacy is given to us at birth, we learn to shape its meaning over time. It may simply be the art of questioning and finding our own answers. Always, it remains a movement: a living dialogue between history and possibility.

Inspired to travel to Lamu? Start exploring your trip with us today!